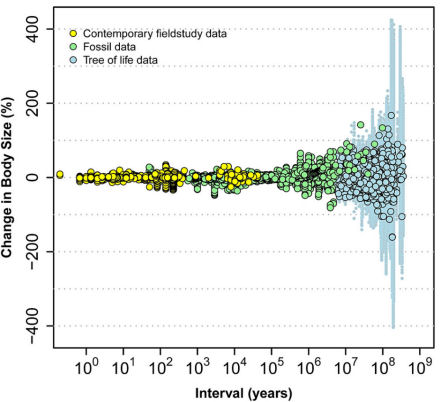

Addressing the long-running debate about short-term vs. long-term evolutionary change, a new study in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences suggests that the changes that stick tend to take a long time, and one million years appears to be the magic number.

The findings show that rapid changes in local populations often don’t continue, stand the test of time or spread through a species. In other words, just because humans are two or three inches taller now than they were 200 years ago, it doesn’t mean that process will continue and we’ll be two or three feet taller in 2,000 years.

“Rapid evolution is clearly a reality over fairly short time periods, sometimes just a few generations,” explained Uyeda. “But those rapid changes do not always persist and may be confined to small populations. For reasons that are not completely clear, the data show the long-term dynamics of evolution to be quite slow.”

Across a broad range of species, Uyeda found that for a major change to persist and for changes to accumulate, it took about one million years. He adds that this occurs repeatedly in a remarkably consistent pattern. “What’s interesting is not that we have so much biological diversity and evolutionary change, but that we have so little,” he said. “It’s a paradox as to why evolution should be so slow.”

“This isn’t just some chance genetic mutation that takes over,” he cautions. “Evolutionary adaptations are caused by some force of natural selection such as environmental change, predation or anthropogenic disturbance, and these forces have to continue and become widespread for the change to persist and accumulate. That’s slower and more rare than one might think.”

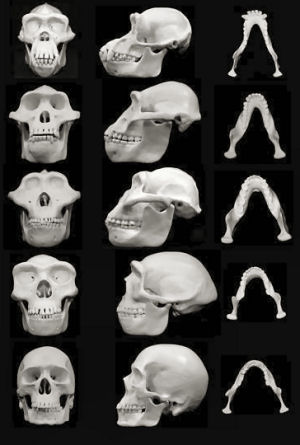

Though slow, however, the process appears to be relentless. Most species change so much that they rarely ever last more than 1-10 million years before going extinct or developing into a new species, the study notes.

The study is one of the first of its type to help reconcile the rapid evolution seen by biologists in contemporary species; the slow, stable changes observed by paleontologists; and dramatic, macroevolutionary differences in body sizes.

Related:

Unnatural selection: Courtesy of The Pill

Revealed: new player in natural selection

Samoan study reveals possible evolutionary role for homosexuality

Comments are closed.