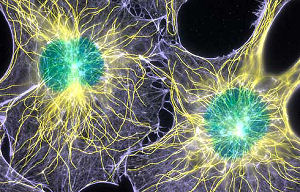

A previously hidden mechanism that guides the way biological organisms respond to the forces of natural selection has been observed making the proteins found in most living organisms behave like adaptive machines, subtly directing aspects of their own evolution to create order out of randomness. Researchers Raj Chakrabarti, Herschel Rabitz, Stacey Springs and George McLendon made the discovery while carrying out experiments on the proteins constituting the electron transport chain (ETC), a biochemical network essential for metabolism.

A subsequent mathematical analysis of the experiments showed that the proteins themselves acted to correct any imbalance imposed on them through artificial mutations and restored the chain to working order, explained Princeton University’s Chakrabarti.

“The discovery answers an age-old question that has puzzled biologists since the time of Darwin: How can organisms be so exquisitely complex, if evolution is completely random, operating like a ‘blind watchmaker’?” said Chakrabarti. “Our new theory extends Darwin’s model, demonstrating how organisms can subtly direct aspects of their own evolution to create order out of randomness.”

The new research, published in Physical Review Letters, provides corroborating data for Wallace’s idea. “What we have found is that certain kinds of biological structures exist that are able to steer the process of evolution toward improved fitness,” said Princeton researcher Rabitz. “The data just jumps off the page and implies we all have this wonderful piece of machinery inside that’s responding optimally to evolutionary pressure.”

To try and identify the underlying mechanism for this self-correcting behavior the researchers are applying the concepts of control theory, a body of knowledge that deals with the behavior of dynamical systems. The researchers concluded that this self-correcting behavior could only be possible if, during the early stages of evolution, the proteins had developed a self-regulating mechanism, analogous to a car’s cruise control or a home’s thermostat, allowing them to fine-tune and control their subsequent evolution. The scientists are working on formulating a new general theory based on this finding they are calling “evolutionary control.”

The new work is likely to trigger a rethink of evolutionary dogma which maintains that species evolve because of random mutations and selection by environmental stresses. But unlike Darwin, Wallace conjectured that species themselves may develop the capacity to respond optimally to evolutionary stresses. Until this work, evidence for this conjecture was lacking.

The experiments themselves focused on a complex of proteins located in the mitochondria, the powerhouses of the cell. A chain of proteins, forming a type of bucket brigade, ferries high-energy electrons across the mitrochondrial membrane. This metabolic process creates adenosine triphosphate (ATP), the energy currency of life. Various researchers working over the past decade fleshed out the workings of these proteins, finding that they were often turned on to the “maximum” position, operating at full tilt, or at the lowest possible energy level.

Chakrabarti and Rabitz analyzed these observations of the proteins’ behavior from a mathematical standpoint, concluding that it would be statistically impossible for this self-correcting behavior to be random, and demonstrating that the observed result is precisely that predicted by the equations of control theory. By operating only at extremes, referred to in control theory as “bang-bang extremization,” the proteins were exhibiting behavior consistent with a system managing itself optimally under evolution.

“In this paper, we present what is ostensibly the first quantitative experimental evidence, since Wallace’s original proposal, that nature employs evolutionary control strategies to maximize the fitness of biological networks,” Chakrabarti said. “Control theory offers a direct explanation for an otherwise perplexing observation and indicates that evolution is operating according to principles that every engineer knows.”

The scientists do not know how the cellular machinery guiding this process may have originated, but they emphatically said it does not buttress the case for intelligent design, a controversial notion that posits the existence of a creator responsible for complexity in nature.

Chakrabarti said that one of the aims of modern evolutionary theory is to identify principles of self-organization that can accelerate the generation of complex biological structures. “Such principles are fully consistent with the principles of natural selection. Biological change is always driven by random mutation and selection, but at certain pivotal junctures in evolutionary history, such random processes can create structures capable of steering subsequent evolution toward greater sophistication and complexity.” The researchers are continuing their analysis, looking for parallel situations in other biological systems.

Related:

1st Rule Of Evolution: Strive For Complexity

Researchers Ponder Primordial Broth

Turbocharged Evolution

Prof Questions Darwinian Dogma

Darwin’s Dilemma Solved?

Promiscuous Proteins Provide Evolutionary Shortcuts

Comments are closed.